It is not because I was burned by a bigger world. There was never anything to give up on, except a marriage, and that was less about giving up than about acknowledging a truth there all along. The world has scared me but it scares me less now. It might be because I am older and will only get older than I am now. It might be because my parents are older and will only get older than they are now.

I can live other places, have proven, at least this, to myself. Boston and New York part-time and North Carolina and Buenos Aires and Singapore and New Orleans. Places on a map full of places. Arbitrary boundaries. When I left Lake Providence for Duke, I wondered how the bigger world would feel. I thought it would be an extension, but it felt instead like something entirely different. Another planet, perhaps. Years later, flying home, through Atlanta and then onto Monroe, I spotted the lake I grew up on from my window seat. I knew its shape instantly and so spotted the John Deere store, the places on the lake where my grandparents lived, where I’d lived, the levee and the burned down downtown. I could see the whole of it from 30,000 feet. And so of course it had felt like a different planet because it was small and it had felt so whole.

There were places along the way that awakened parts of me enough to believe that I might find wholeness elsewhere. A documentary studies center at the edge of Duke’s campus; my little South End apartment on girls’ nights; runs along the Hudson River. Something like it on a tree-lined street in Buenos Aires peppered with dog mess and a grocer and pasta maker and cobbler and fruit vendor and flower vendor who knew my name; in a wet market a bike’s ride away from my Singapore apartment and on my good friend’s balcony where I was served the best margaritas of my life. There was a time I envisioned a child calling me Mama in a Spanish accent. A time I resigned myself to the fact that my family wouldn’t meet my baby until the two of us could make the 36-hour trek to their Louisiana doorstep, flying from Singapore through Moscow or Dubai or Tokyo to get to them. There were times in which I was sure I’d be standing in front of a college classroom teaching first-years how to write a good essay while I tried to shut their words out in the early mornings enough to write my own. And some part of me still longs for the rhythms of New Orleans to be mine again. Real lives. They all might have been mine. At the time of my imagining, I could feel them. At night, in my dreams, I was already living them.

And then of course there were the hills and mountains and shores of New Zealand. A home there, perhaps. A Japanese village so quiet and serene it seemed like I’d been there before everything else, like it might hold me in that space forever. There was Salta in Argentina where it was all possible.

Life’s ability to surprise continues to be one of the reasons I am grateful to wake up in the mornings. The man I married second and I, friends since childhood, found each other in the most unlikely way. It is nothing we could have imagined as children across the table from each other at Ms. Martha’s daycare, and then again, much later, on the football field where he threw and I cheered and at the boat landing where we hung out with our friends. Who I was then, that girl, and then who I was when I got on a plane from Singapore to New Orleans with my hair on fire– there must have been a few lives between them. All of them real and unreal at the exact same time, unknowable, yet they happened. Here were photographs, emails, an angel from a store on the beach at Punta del Este on Christmas Eve, a Hindu figure from a temple deep in the woods of Ubud. I had loved and hurt and it was all gone and it had indeed all happened.

Later still, I was home for the weekend in the middle of a back and forth over whether we would move to Denver for his life or New Orleans for mine. I wrote about that weekend later, trying to understand what was happening, sent it to my friend, my high school English teacher who knows all there is worth knowing about me and a few things that aren’t. That weekend I had gone to church with my parents, sat on the pew where my mother’s father always sat. I remembered his shaky hands passing the communion plate near the end of his life. I remembered going to the church on my last stop in town before I went to New Orleans to marry the first time. I had sat in the pew and cried then, acknowledging, without understanding, all that I was letting go of, all I was saying goodbye to. Not understanding how unready I was to do so, how wrong, on the cellular level, it was to do so. It was all different now but there was my dad’s mother in the pew in front of me, still. Singing. Back of her neck visible to me where she had attached magnetic closures to her necklaces because her arthritic hands won’t allow her to do the clasps anymore. She’s angry about all of this though I think behind that is just a lot of sadness. Later that day I rode with her to Greenville to pick up poinsettias for the front of the church on Christmas Eve. We laughed and talked. I told her about Pete. She said I should not consider how happy or unhappy this made my parents (whose best friends were Pete’s parents). I photographed my nieces that weekend. Marveled at their growth. Babies when I left and now rational, self-conscious, still young enough to be somewhat free. Beautiful, in every way. The end of the email: “I don’t know what it is. A desire to be around my parents. To know my nieces and Houston. Give to a community. Be a part of it. I’ve lived in places where people moved in and out. And I’ve been in places where the connections are deeper and more stable and they are not so different from Lake Providence in that there are going to be people to connect with, going to be people to not. My longing for the real hasn’t changed. Knowing people’s stories helps make things feel real for me. I don’t know that I could do it but I am thinking about it.”

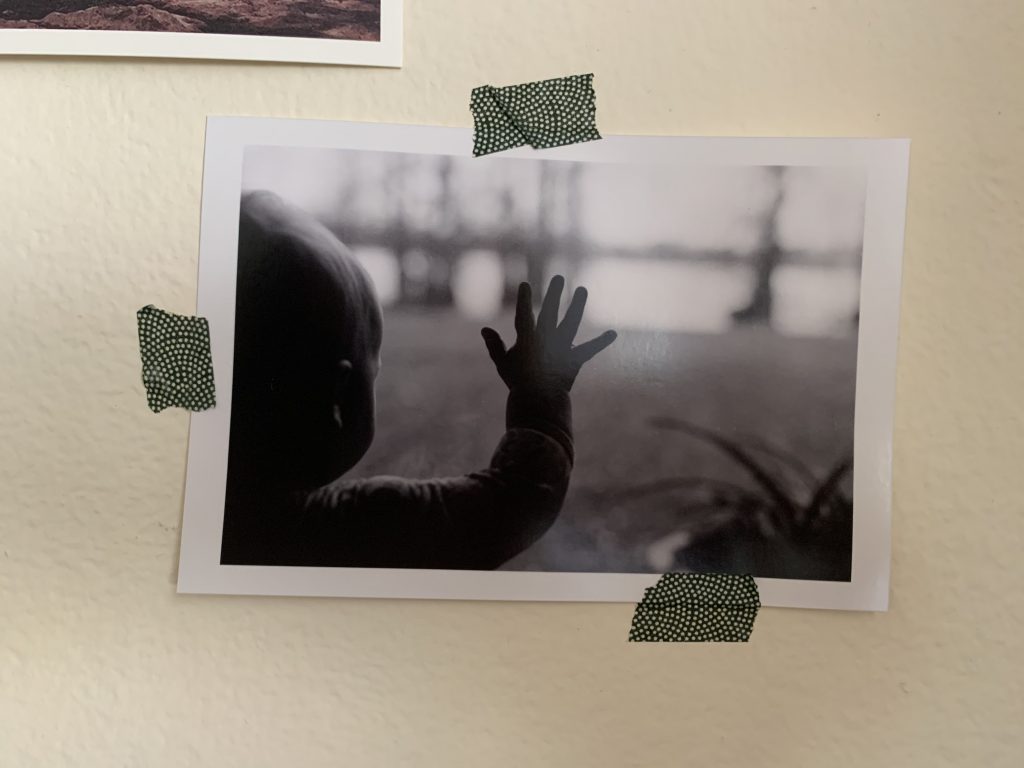

And then we did it, together. Which is of course the only way it could be done. A 1952 well-loved home that we kept in tact and made ours. We have a daughter now, almost one. She sat on a two-day old mule colt the other day and the next was held by her grandfather while the other one used some complicated machinery to fill my garden beds. Her grandmothers adore her, and she them. I take her to watch my nieces play every kind of ball and children and adults alike tell her hello, call her by name, and reach out their hands to touch, kiss, hold her. She has what we had. It’s a safe place and she knows a lot of love.

There is another part of the answer too, to why I moved home. I don’t tell many because it reveals a bit too much about me. It says things I don’t like to give away because it’s mine. But it’s also the truth. This little town that raised and formed me and set the foundation for all that was to come— it’s a place with deep poverty and prejudice and struggling schools and bitterness and pessimism and a hell of a lot of pain. Most people here don’t vote like me, don’t interpret the Beatitudes the same way that I do. If they knew how deeply I felt, they’d accuse me of being something I’m not. A snowflake, perhaps. Some bleeding heart. Some are so far from me politically and ideologically that if we were caricatures of ourselves in some news story we would spit nothing but disgust at each other. But we share meals and hurts and victories and go into each other’s homes. We sit in pews near each other and I know about their daughter’s cancer and father’s fall and all the other traumas. And they bring me meals when I have a baby and wave at me when we pass on the road. My body can ache with what I perceive to be their indifference or their selfishness and I have seen their bewilderment at what my idea of justice is and the things I think are possible that indeed may not be possible. This is part of it: Trump was elected the fall before I moved home. Most of the people I’ve loved since I was a child voted for him. They are good people. I needed not anymore to put myself in another bubble, a different bubble where everyone thought as I thought, voted as I did. I learned in my travels that comfort zones take things from you– vitality and connection to your soul, for example.

There is so much work to be done. I almost never sleep through the night anymore and it isn’t my daughter’s fault. I like to think she sleeps so soundly because of what her dad and I are determined to do for her. Give her a home, a safe place, a place to rest, a place to come back to. Not any place either. This place. This water and this sky and this dirt. This piece of history, this responsibility. It’s uniquely ours, is uniquely hers now. I’ll get her out when I can. Show her what else there is so that she too may choose to go out into it and to love people from other places and make friends who fill her up and see things that make her weep and bring her joy and expand her mind and heart.

It did all those things for me. Continues to. We leave for Boston Saturday, she and I. Her first birthday trip. The trip is for me, of course, but it’s for her. I’ll have real talks with my friend there. She’ll see tall buildings and soon forget them. It’s been a hard year. My husband had to leave for work when she was three days old. Our house still, at 6pm when it is just she and I, can be the quietest and loneliest place I’ve ever known. An uncle I loved dearly died suddenly and left all of us before he should have and now his absence stalks and haunts us. My uncle got older and life did what it does— it took. We lost and we’ve seen each other through it and there were nearly unbearable days of having to look each other’s pain in the face. I’d have liked to have run. But there it was again. It’s a small town. You cannot hide. But life gave too. We gained. And I think of him sitting at my dining table just a few days before his death and I think of him sitting in the chair talking to me and admiring her just a few days after her birth. And now I see her with my aunt, a mutual admiration. We lost and we gained and all the while my daughter grew and grew and that’s all she had to do, thank God.

So I’m still working it out. We’ll call this part one of the answer to why I moved home. Or, rather, version one. People wonder how I do it, why. Such a small town and of course they mean small thinking and small opportunity too. It is indeed a small town. With problems not so small. But I saw versions of them everywhere I lived. So what matters, my husband and I asked? What really matters? I know now that you can’t force things to be what they are not, learned the hard way, so how do you find the truth and follow it and squeeze the best you can from it?

Perhaps it’s what Wendell Berry says: “Slow down. Pay attention. Do good work. Love your neighbors. Love your place. Stay in your place. Settle for less, enjoy it more.”

Pete and I like two roads best and we drive them often. One leads to the farm my grandfather cleared and my dad farmed. The other leads to the farm his grandfather cleared and his dad farms. It matters how much our daughter loves her grandparents. What else? Matters that we share meals with them, often, and they see us now as adults and as parents and we see them now as real people with most of their lives behind them which breaks our hearts and makes us ever more grateful. Matters that we have all been there for each other. Matters that we can talk about the difficult things with people like and unlike us, our definitions of like and unlike altering all the time. That we are restoring an old home, that we can ride a horse and do some good and act up and be forgiven and forgive others. I believe what I’ve been told. What helps one of us helps all of us. The world can be better, should be better, and why not start at home. We can be good to our parents and our siblings and be good to each other and good to our daughter. We can confront what’s hard and find some way to grow. We can have a glass of wine on the back porch and throw crawfish heads in the lake and drink a beer on the levee. We can be better and we can have fun and we can misbehave and we can love the people we love the best we can and it seems right to start at home.